Supporting out-of-school girls and marginalised groups

Strategies for reducing the numbers of out-of-school girls and children

from marginalised groups in the ASEAN region.

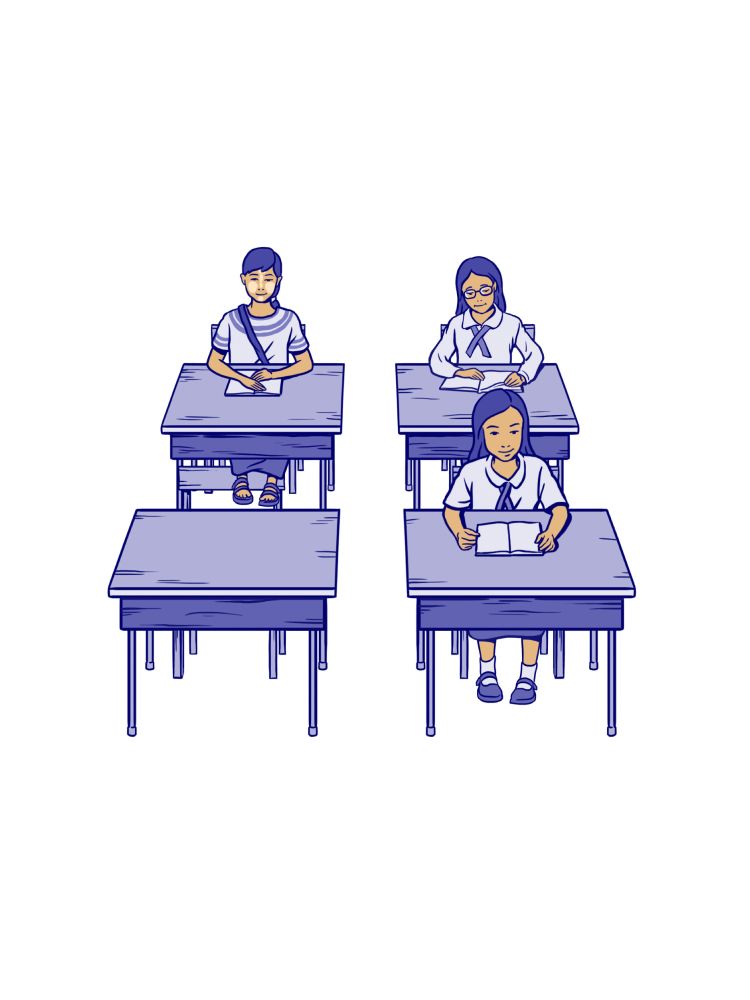

There are 18 million children and youth out of school despite considerable efforts towards universal primary and secondary education in the ASEAN region. Out-of-school rates have dropped in many countries and gender gaps in access and completion are closing. But too many children still miss out on their education and its lifelong benefits.

Although the situation for girls has improved dramatically, many pockets of disadvantage exist and persist. These are most pronounced in the newer ASEAN member states.

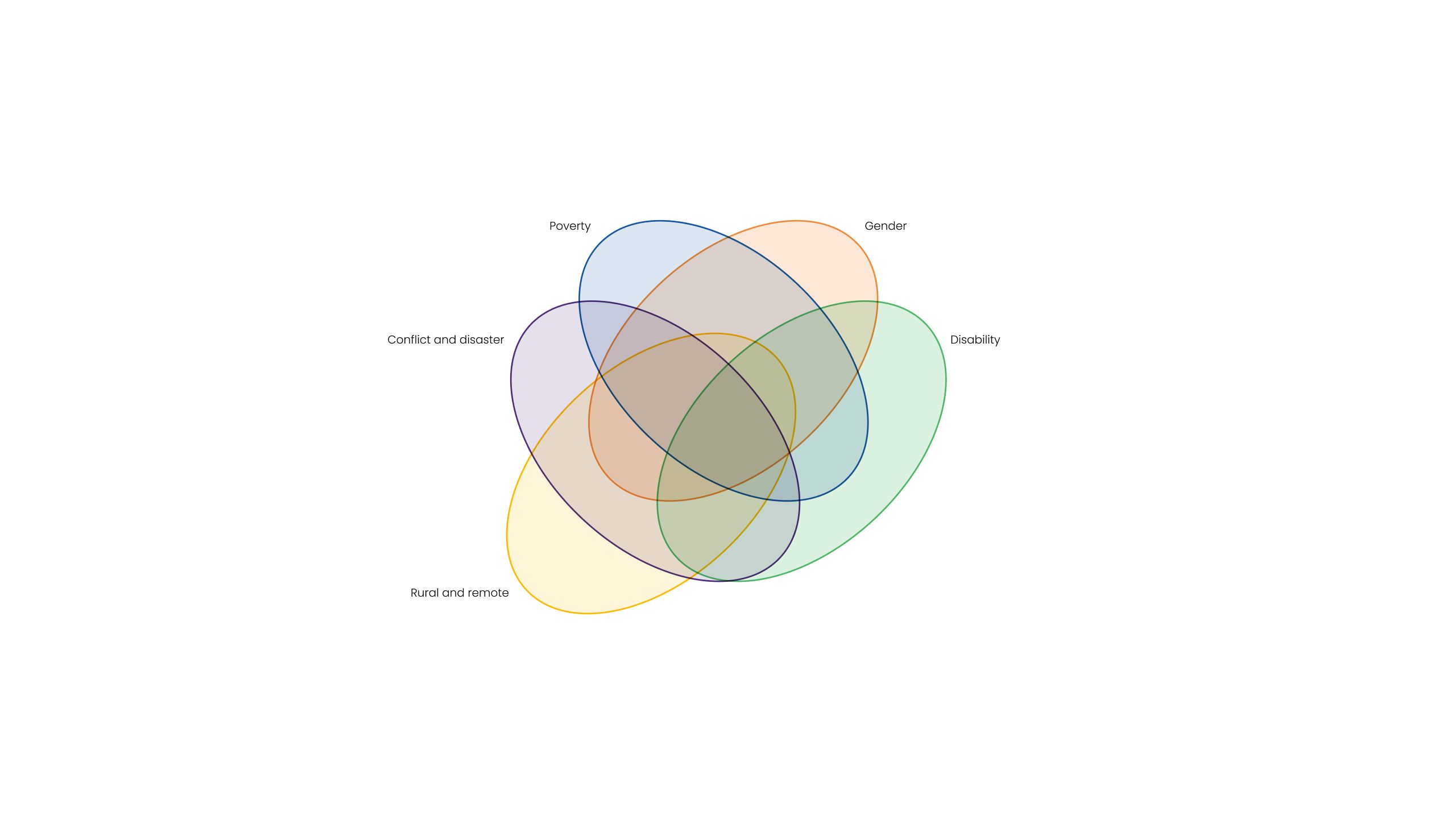

Out-of-school girls, and children and youth from marginalised groups face many barriers to participating in education across their lives. When poverty, rurality, linguistic background, disability, and the threat of conflict and disaster overlap, meeting the unique education needs of these groups is even more difficult.

Initiatives that focus on retention and achievement are needed in tandem with support for engagement and learning to ensure at-risk groups have the best possible chance to not only stay at school, but to achieve at school.

Every year of learning that a person achieves equates to about a 10% increase in their annual earning capacity; this is higher for women and highest in lower-income countries. But the value of education is much more than increased earning potential. The wide-ranging social and economic benefits extend beyond individuals to empower their families, communities, and future generations.

The ASEAN-UK SAGE Programme will invest in evidence-based initiatives to respond to the needs of out-of-school girls and marginalised groups, deliver far-reaching returns for the region, and close the development gap across and within ASEAN member states.

The situation for out-of-school girls and marginalised groups

Great leaps have been made in the past 15 years to reduce out-of-school rates, increase completion rates and close the gender gap at all education levels across the ASEAN region.

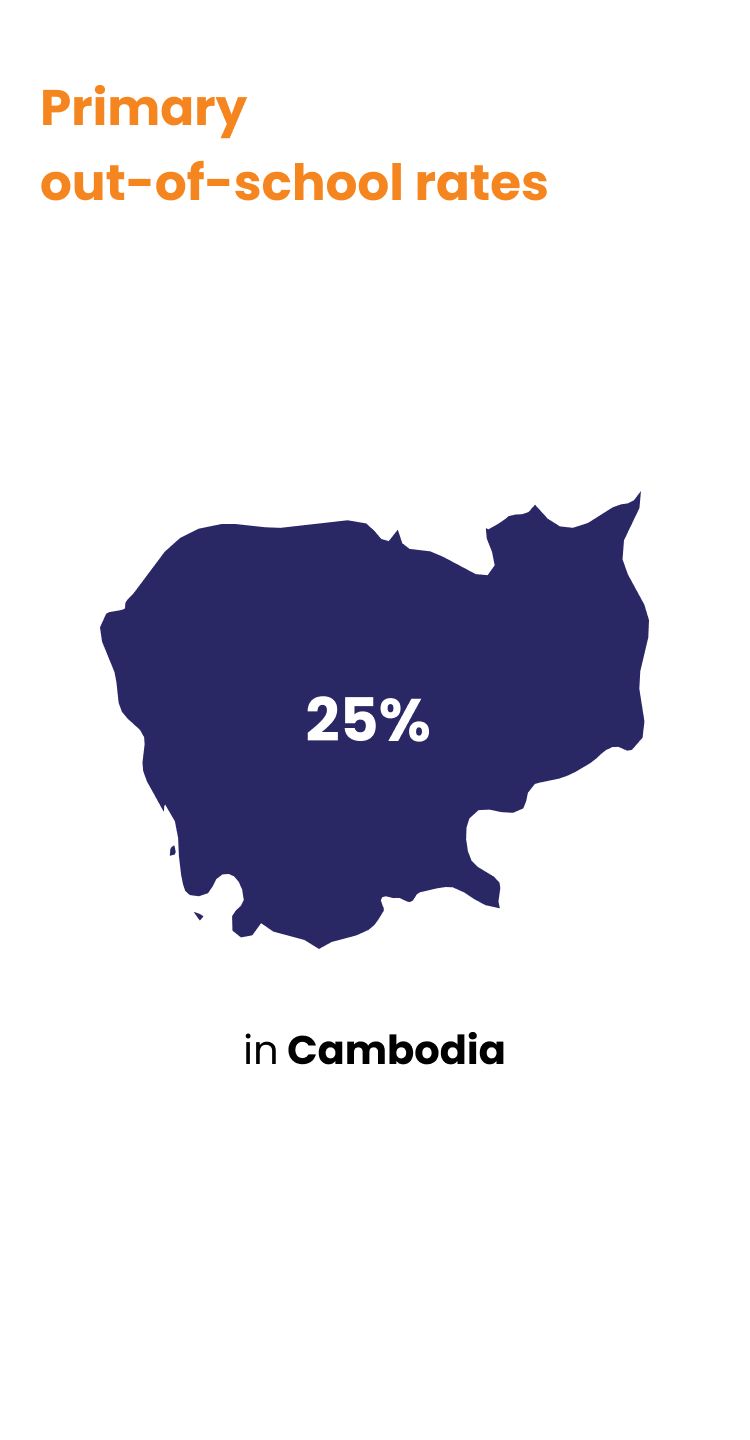

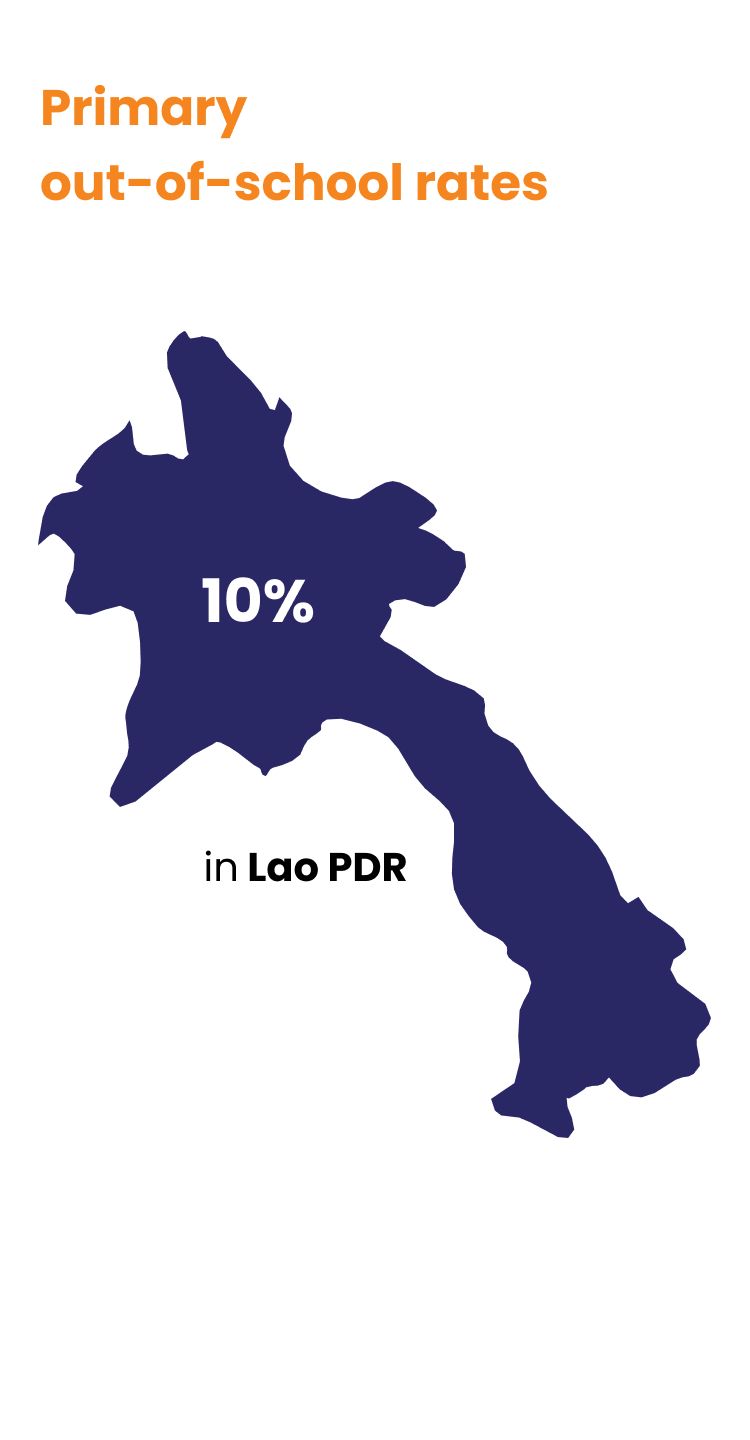

Cambodia, Myanmar, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR) and Timor-Leste, countries with the highest historical out-of-school rates, have made the most significant progress. Lao PDR reduced its primary out-of-school rate from 26% in 2000 to 10% in 2017, and reached gender parity in school completion.

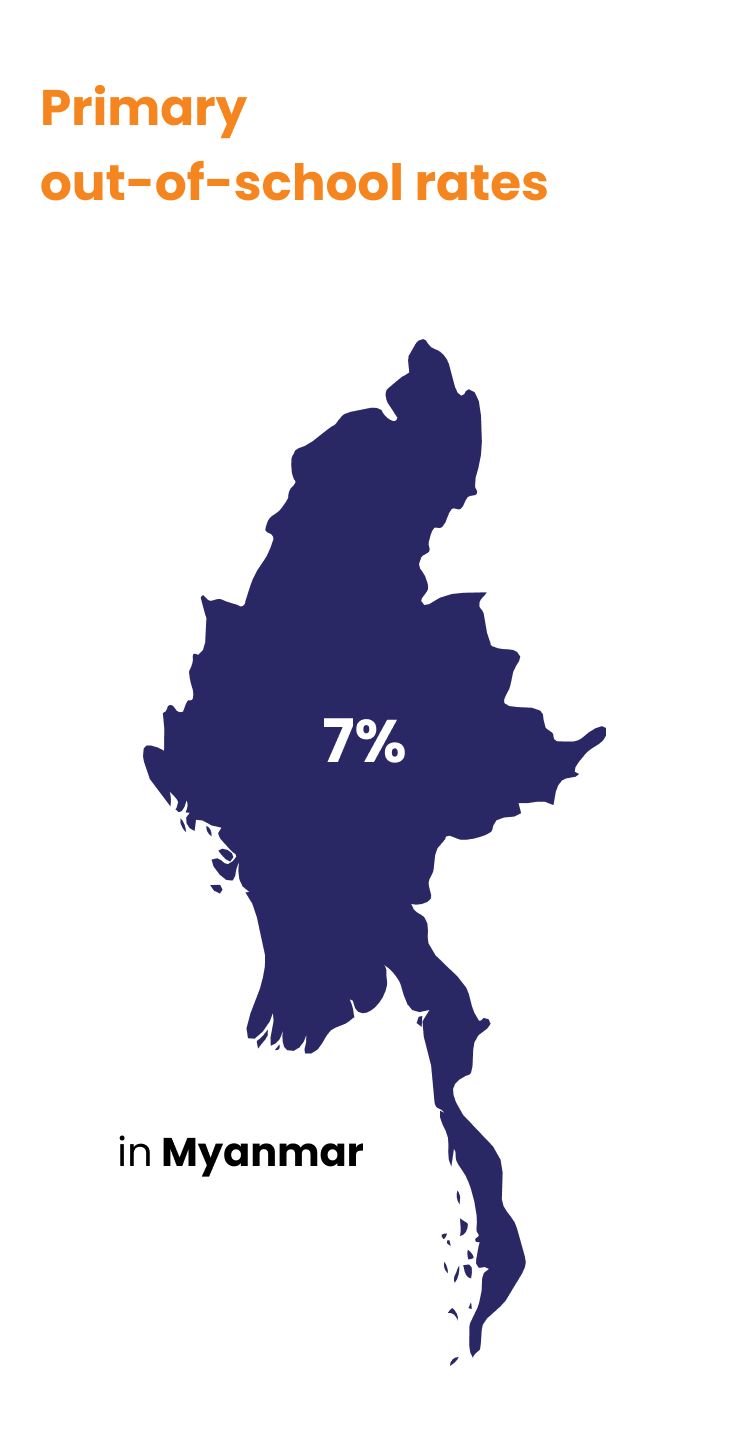

Cambodia also reduced its primary out-of-school rate, decreasing from 27% in 2000 to 7% in 2014, and reversed the gender gap, with higher numbers of girls completing than boys. This trend for girls continues across lower-secondary and upper-secondary and is similar in Myanmar, Timor-Leste and the remaining ASEAN countries.

The gender story is not simple nor straightforward. Where data for background characteristics is available, a more nuanced picture emerges. In Lao PDR, despite gender parity in primary completion rates, more rural children, girls from the poorest households and non-Lao Tai children are out-of-school.

Data shows concerning levels of children and youth not completing lower-secondary and upper-secondary schooling. While primary completion rates hover around 80% in Cambodia, Myanmar, Lao PDR and Timor-Leste, rates fall to just over 50% in lower-secondary. While half of students complete upper-secondary in Timor-Leste, only 20-30% in Cambodia, Myanmar and Lao PDR do.

Both genders still combat distinct challenges when it comes to completing school. Older out-of-school children and youth are often expected to earn an income for their families. Early marriage and caring responsibilities often impact girls. In these contexts, it is difficult to recommence or engage with schooling.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is yet to be fully understood. Regionally, girls and the most marginalised were hit hardest; extended school closures widened pre-existing opportunity and achievement gaps.

Where 2022 data is available, it shows that out-of-school rates increased, particularly for younger children. In Cambodia, while primary out-of-school rates have fallen since 2000, data now shows these wins have been lost. Enrolments have also fallen in Thailand and the Philippines, particularly for the poorest. Any gains made are fragile and have to be protected.

Despite these challenges, 10 out of 11 ASEAN countries have reported a reduction of their expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP in recent years.

Only by ensuring that all children complete all years of their education across all countries in the ASEAN region will the ambitions of narrowing the development gap be met.

Challenges to supporting the most marginalised

We need to identify and understand the profiles of out-of-school girls and marginalised groups to effectively support them. This is challenging for many reasons.

Defining out-of-school and marginalisation

There is a lack of agreement among education stakeholders on the concepts of out-of-school and marginalisation, including gender equity. Terms such as ‘disadvantaged’ and ‘hard-to-reach’ are used interchangeably with ‘marginalisation’. There are also different understandings of the dimensions of out-of-school children and youth. For example, the ASEAN Declaration on Strengthening Education for Out-of-School Children and Youth (2016) focuses on access and participation, while others include engagement and learning. These different definitions illustrate the complexity of responding effectively, and risk excluding the most marginalised.

Measuring who is out-of-school

Collecting data on out-of-school populations has historically been difficult due to incomplete and often inaccurate education data. Regional and national numbers can mask lower-level trends and exclusions, especially of the most marginalised children.

Disaggregated data can be limited and there are concerns around quality. While data on location and socioeconomic status are increasingly available, information on ethnicity, language, disability, LGBTIQA+ and migration status, is more difficult to collect and measure.

Combining multiple data sources, including household survey data, can provide more accurate estimates.

Responding to marginalisation

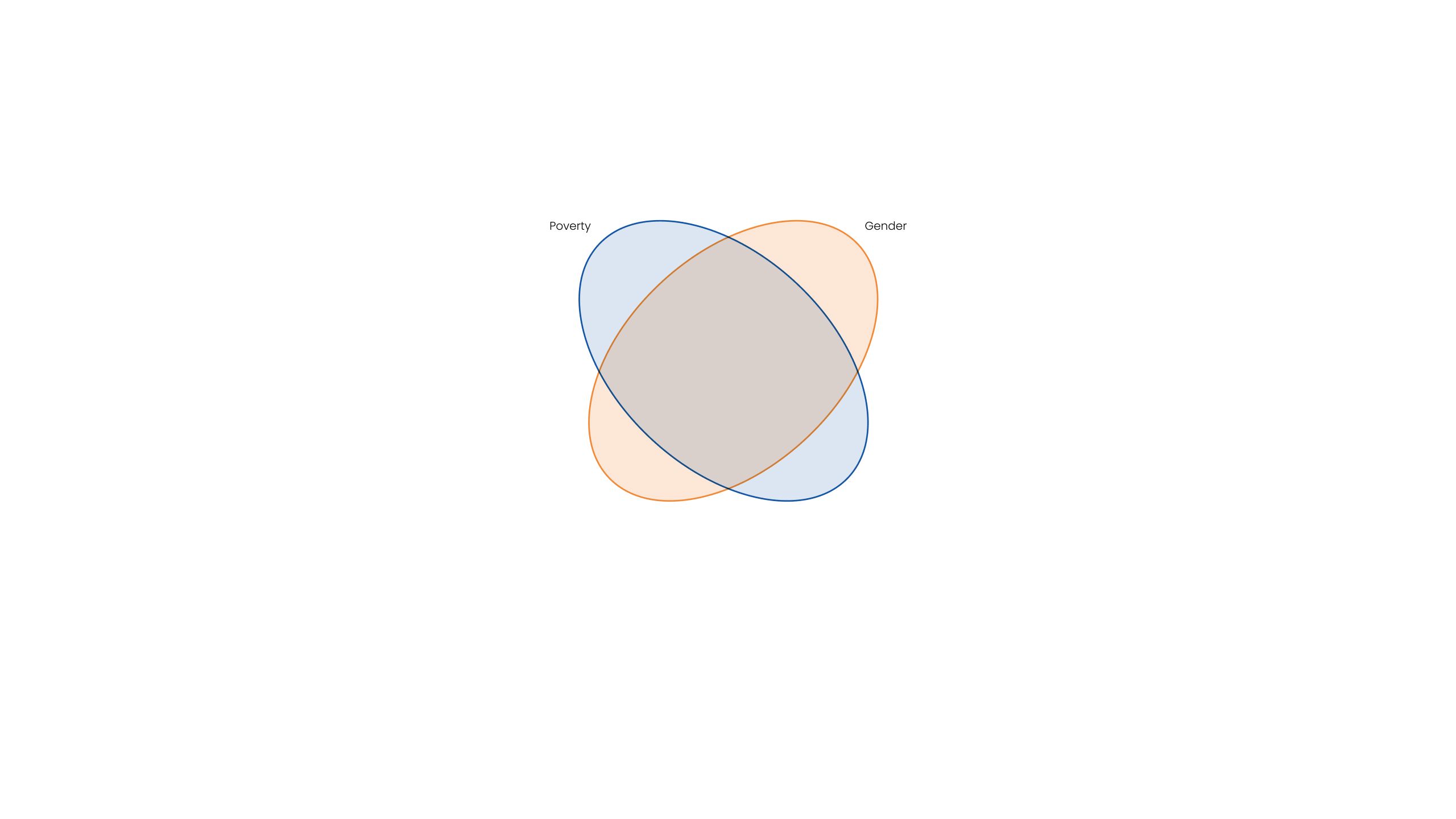

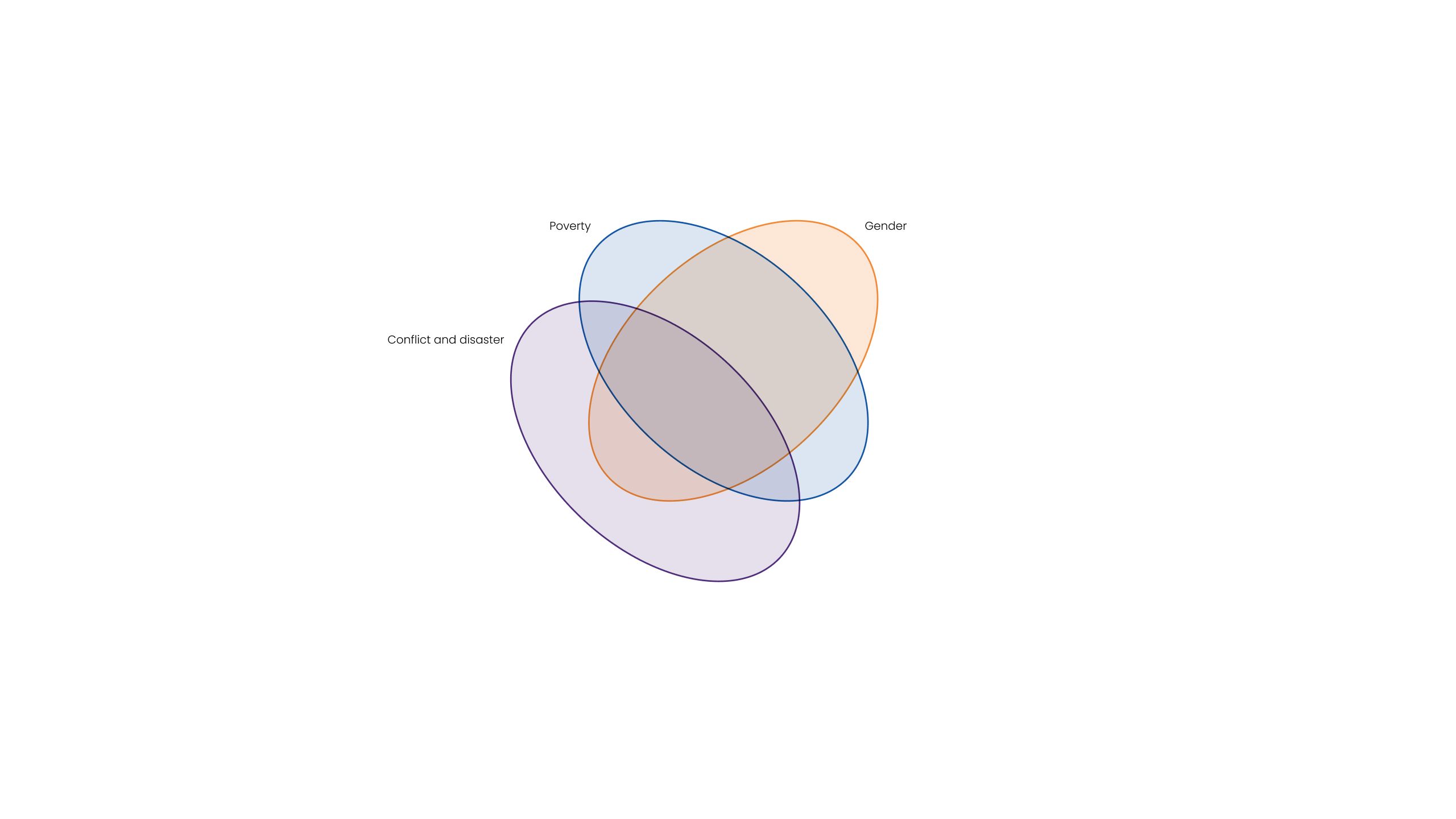

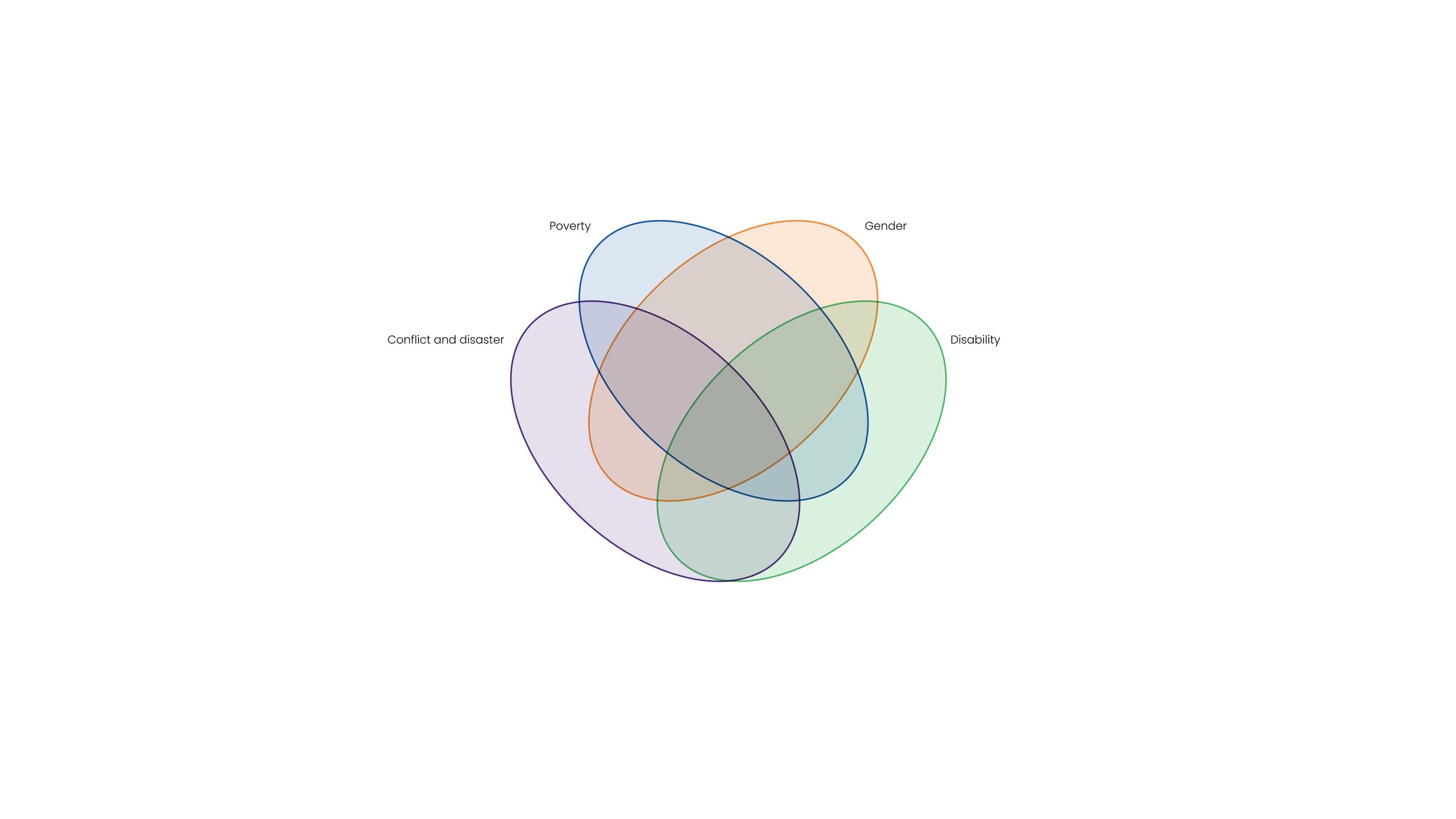

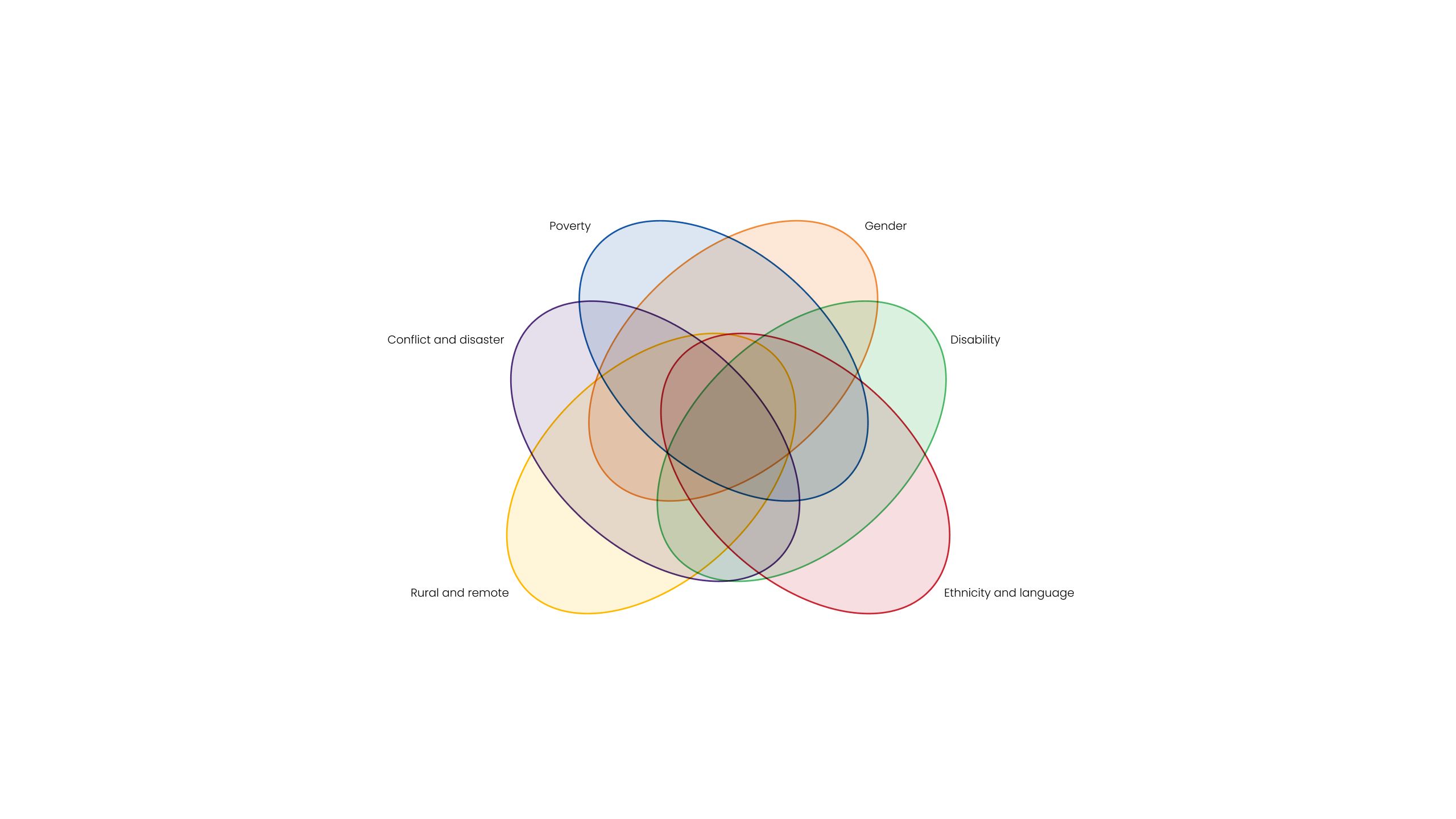

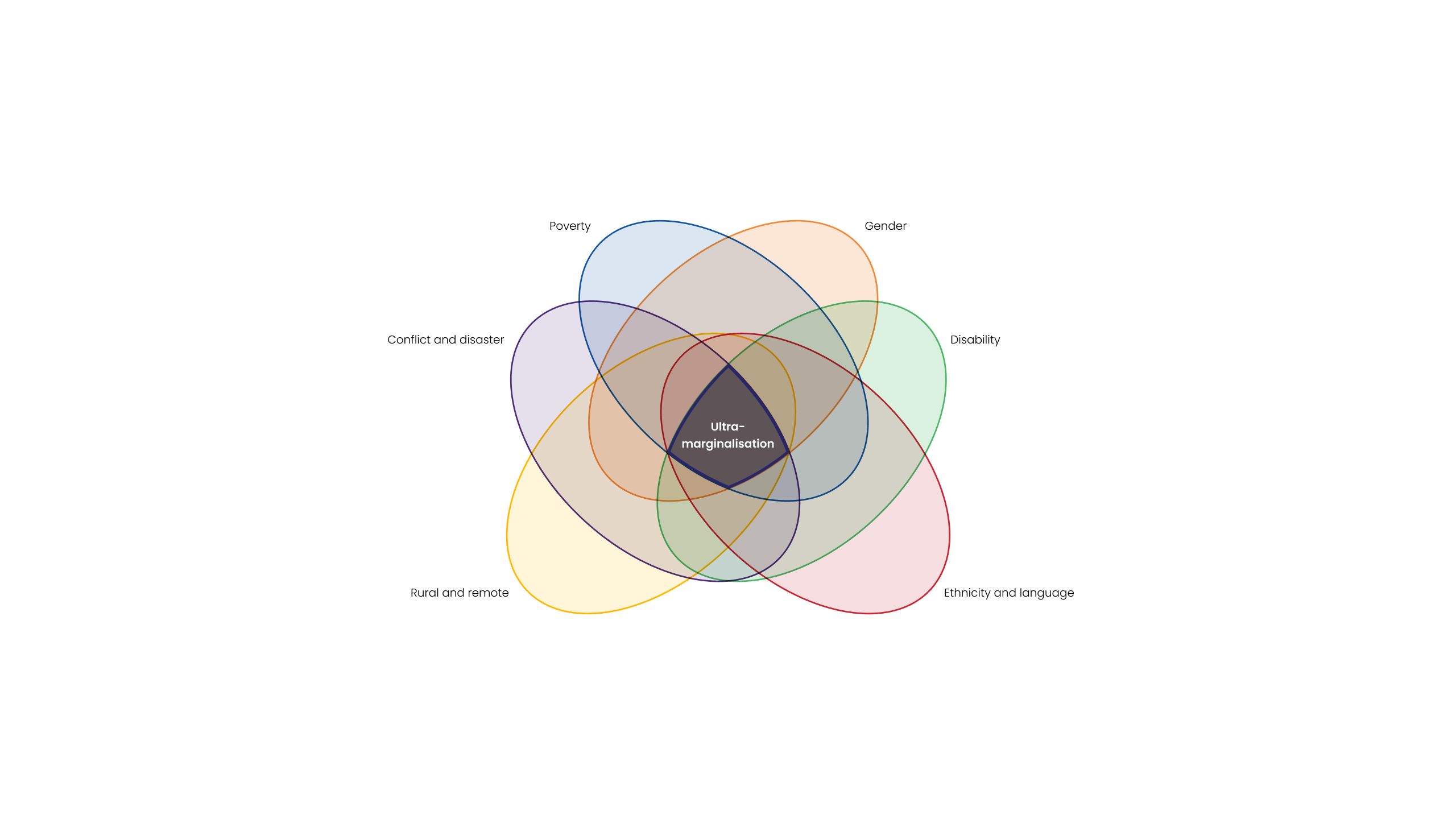

Understanding the overlap between factors that shape the individual experiences of children and youth can lead to better-tailored policies and initiatives. These factors cannot be considered in isolation.

Barriers to accessing and staying in school

Across the ASEAN region, many factors lead to children dropping out of school, or not attending in the first place. Unique barriers can prevent girls and marginalised groups from accessing and completing their education. Their support needs become even more complex when areas of marginalisation overlap. Ultra-marginalisation occurs when there is overlap between one or more areas.

These can relate to individual and family circumstances, as well as community, school and policy factors.

Poverty

Children from the poorest households are at greatest risk of dropping out of school. This is even more pronounced as children move into secondary education when there is pressure to work, and for girls in particular to care for others and marry. Families experiencing extreme poverty are more likely to send boys to school than girls. They are also less likely to provide support to learning at home.

Girls from the poorest families in Lao PDR are most likely to be out of school at all levels of education – their out-of-school rates are double national levels.

Poor learning

Foundational learning outcomes are lowest for children from disadvantaged contexts. Children become disengaged and de-incentivised to continue their schooling when they do not learn. If children are not learning in school, they do not stay in school.

In all 6 SEA-PLM participating countries, children from the lowest socioeconomic backgrounds had the lowest levels of achievement in reading, writing and mathematics.

School infrastructure and transport

In many rural and remote parts of the ASEAN region, there are no schools, or at least no secondary schools. Many children have to travel long distances to get to school, which can be determined by parent resources, and can contribute to absenteeism.

Children, especially girls, who travel long distances to attend school are not always safe. Limited basic sanitation and clean water have a greater negative impact on girls' participation, particularly in regards to menstrual hygiene. The absence of accessible school infrastructure creates additional barriers for children with disabilities.

Over the past 15 years, gaps in primary and secondary completion between rural and urban areas have closed; however, in rural Lao PDR, girls are consistently under-enrolled compared to boys.

Sociocultural factors

Gender norms and expectations impact education, career aspirations and roles at home. These perspectives are reinforced early, in the home and community. Children from ethnolinguistic minorities often come from poorer households. These children are more likely to drop out early if their primary language is not the language of instruction. Girls from ethnolinguistic minorities often face additional hurdles related to cultural barriers and discriminatory practices.

In Myanmar, the out-of-school rate for girls at primary school increases from 8% to 24% if they are also from an ethnolinguistic background.

Disability

Negative community attitudes towards disability mean children with disabilities, especially girls, are often kept at home. In addition to a lack of accessible infrastructure and resources, teachers, parents and communities have limited knowledge and skills to embed positive practices at school and in homes.

More than 60% of children with disabilities in Cambodia and Timor-Leste are out-of-school – most have never been to school.

Violence

There continues to be a lack of safe spaces at school, home, in communities and online. There are concerning levels of physical, emotional and sexual violence against boys and girls. Girls face elevated risks of gender-based violence. Girls affected by early marriage and trafficking do not have the same educational opportunities.

Married adolescent girls in Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Timor-Leste and Viet Nam complete around 2 years less school than other girls.

1 in 5 women in Indonesia, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Viet Nam will experience physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner before they are 19 years old .

Conflict and disasters

Conflict and natural disasters can cause school infrastructure damage and closures, and expose children and youth to violence and displacement. Conflict zones threaten the safety of adolescent girls.

Conflict and natural disasters led to more than 2.5 million internally displaced children across ASEAN in 2021.

Promising initiatives

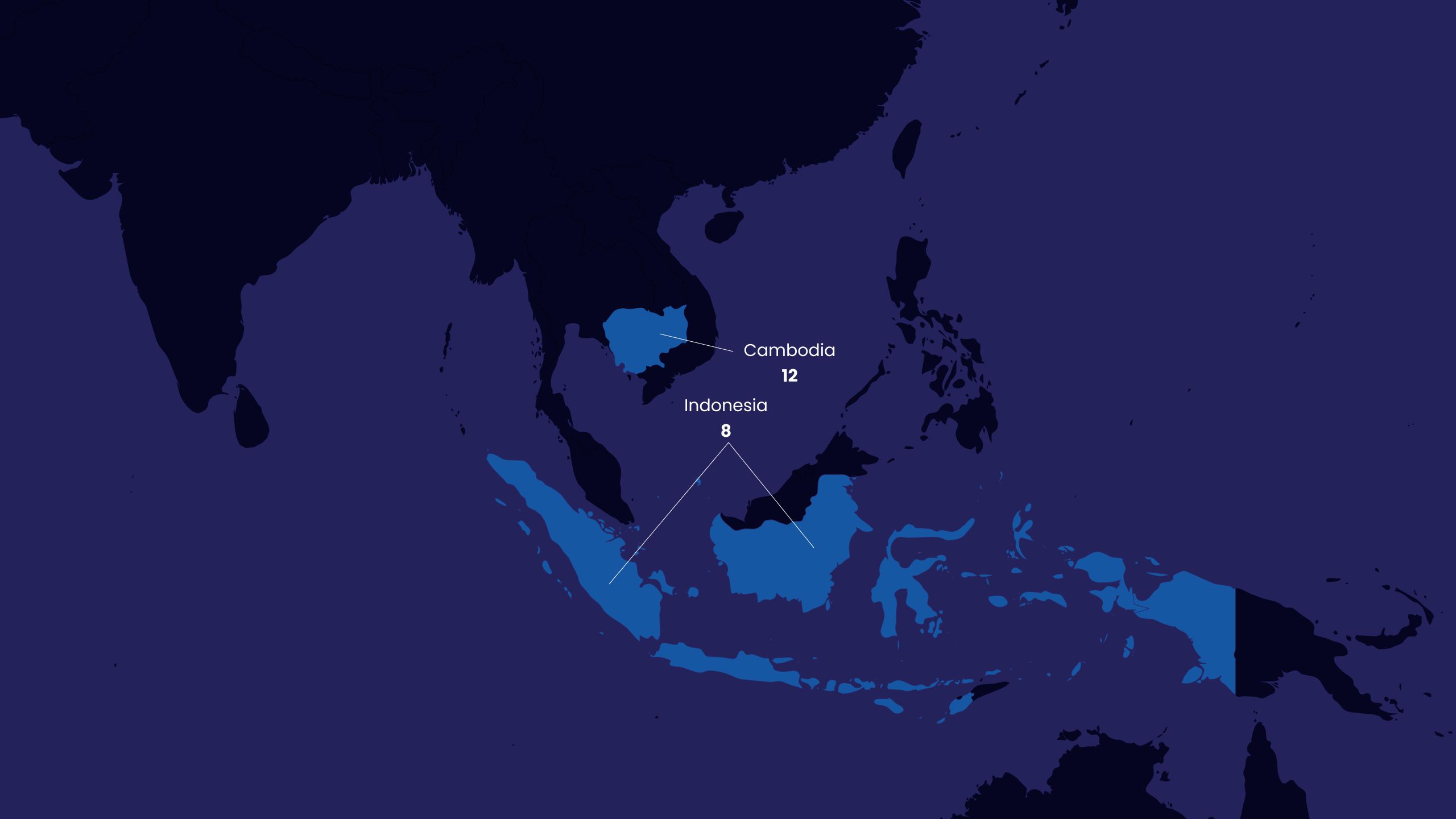

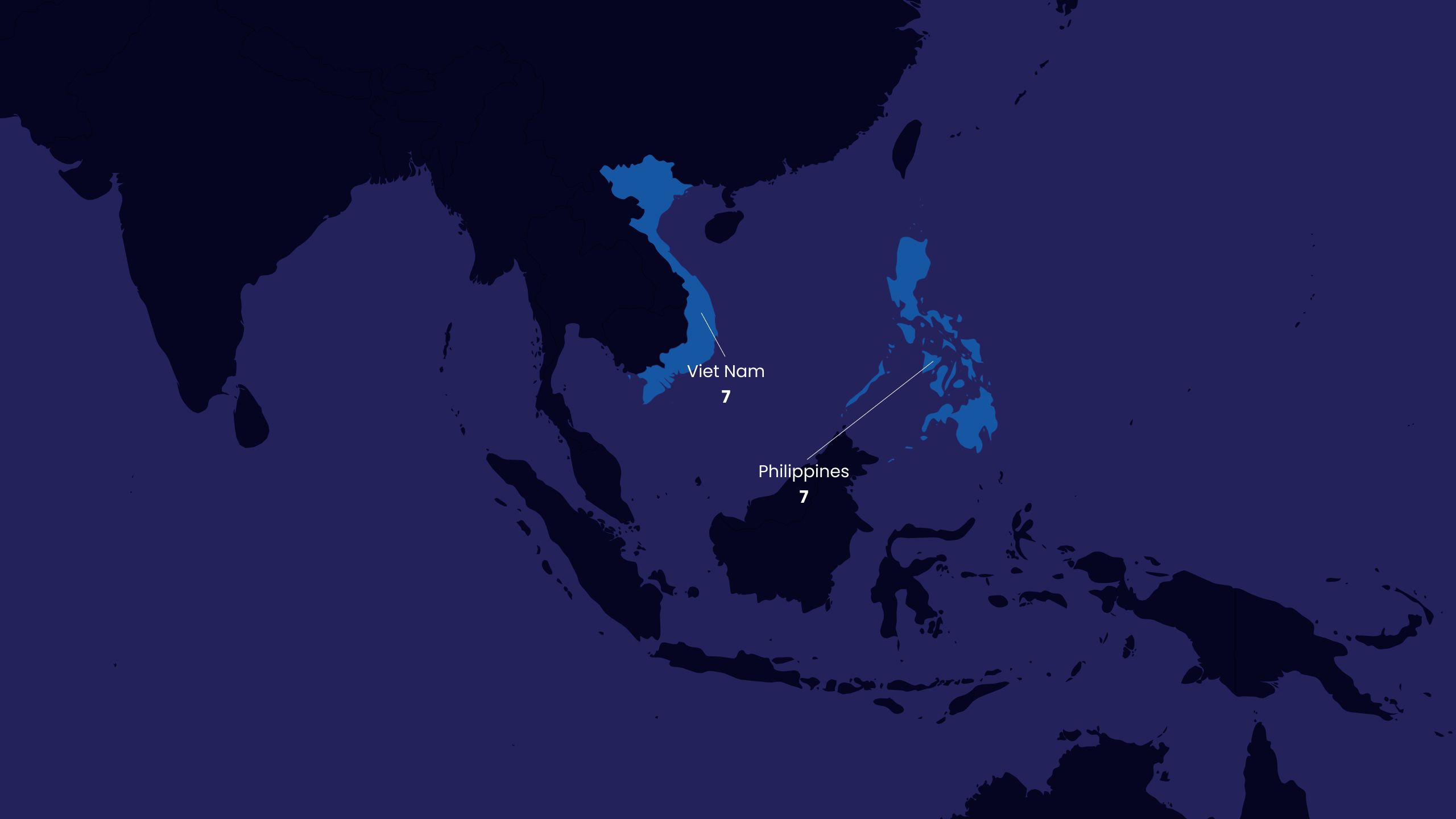

The ASEAN-UK SAGE Programme conducted a comprehensive review of academic and grey literature from 2013 to 2024 to locate high-potential initiatives from the ASEAN region.

While the review identified 48 initiatives, only 18 provided some evidence of effectiveness or information about reach.

Many of the studies are pilots and/or small-scale and focus on retention over engagement and learning. Very few non-formal education initiatives capture evidence of outcomes.

Countries in the ASEAN region have adopted a range of reforms to support out-of-school girls and marginalised children and youth. While not all have clear mechanisms to measure impact, particularly on student engagement or learning, these initiatives are worth exploring.

Policy action

Many countries have adopted legislation and policies as part of their commitment to the 2016 ASEAN Declaration on Strengthening Education for Out-of-School Children and Youth.

Lao PDR ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2009 and is aligned with national laws. Cambodia introduced the Gender Mainstreaming Strategic Plan in Education (2021-25). Myanmar amended the National Education Law in 2015 to include inclusive education.

Data systems

ASEAN countries have taken steps to develop data collection and information systems that allow for early identification of out-of-school children and youth.

In Indonesia, the Wahana Inklusif Indonesia Foundation used an online disability identification program, involving health professionals, teachers and parents, to diagnose 100 students with learning difficulties. The data has helped the Indonesian government to improve the quality of its education database, to support more targeted resource allocations.

Inclusive curriculum and teaching

Governments are recognising the need to adapt curriculum for marginalised groups and support inclusive teaching practices. Girls, ethnolinguistic minorities and children with disabilities are of particular focus for inclusive curriculum.

In Lao PDR, a new primary curriculum has introduced more active and student-centred learning approaches, increasing student interest and engagement. A complementary program to build the foundational language skills of grade 1 students from non-Lao speaking backgrounds has been piloted and expanded.

Accessible infrastructure

Countries have identified the need for minimum standards for accessibility to physical environment, facilities, ICT and services.

In Cambodia, as a part of the 2018 policy on inclusive education, universal design standards were implemented for the construction of school buildings, roads and WASH facilities, making them more accessible for girls and children with disabilities.

Support for schools and communities

Training school personnel, raising community awareness and providing financial incentives for parents are effective components of multi-pronged approaches.

In Cambodia and Indonesia, teachers and principals attended training on gender-responsive teaching. The Learn to Read project in Lao PDR focused on training teachers to identify and provide for children with disabilities in the classroom. In Cambodia, a cash transfer program increased girls’ attendance by 25%.

Alternate pathways

For students who face additional obstacles to remaining in school, access to alternate pathways can help them obtain formal school qualifications.

In Timor-Leste, the Second Chance Education Project focused on developing learning materials and a flexible delivery mode for youth who had been out of the school system for long periods of time. Youth were able to continue learning while attending work, family or other responsibilities.

CASE STUDY 1

Lower secondary education for disadvantaged children in Viet Nam

The Asian Development Bank Lower Secondary Education for the Most Disadvantaged Regions Project used a multi-pronged approach to improve girls’ participation and support marginalised children from 103 disadvantaged districts in Viet Nam. It included a public awareness campaign to challenge social norms and perceptions around girls’ education, a scholarship program for students transitioning to lower-secondary education, and school feeding.

Impact

- increase in net enrolment in lower-secondary from 76% in 2006 to 82% in 2014, including among ethnic minority students

- 50% decrease in female dropout rates

- 44% decrease in female ethnic minority dropout rate.

CASE STUDY 2

School drop out prevention in Cambodia

The USAID's School Drop out Prevention pilot introduced and evaluated the effectiveness of 2 separate initiatives in lower-secondary schools across 6 provinces in Cambodia. The first initiative was an early warning system (EWS) and the second was low-cost solar computer labs.

EWS was implemented across 215 schools to identify at-risk students by monitoring data on attendance, performance and behaviour. The initiative also strengthened school capacity to address the needs of at-risk students, and the partnership between school and families.

Low-cost solar-powered computer labs were installed across 108 schools and provided computer literacy training to improve students’ perceptions of and interest in school.

A robust evaluation analysed 2 years of school-level data from more than 65,000 students and interviewed teachers and students.

Impact

- EWS and solar computer labs reduced drop-out rates by between 5 and 11%

- Teachers and students reported an improvement in teachers’ drop-out prevention practices, and at-risk students’ sense of self-efficacy and responsibility.

Where to next?

In the past decade, there has been significant improvements in school enrolment in primary education across the region, but these gains are fragile. The pandemic, economic crises, conflicts and disasters, disproportionately impact girls and the most marginalised.

The newest ASEAN members face major challenges at the secondary level and beyond. These issues are complex and can only be addressed through a multi-sectoral approach that targets the unique needs of girls and ultra-marginalised groups. All initiatives require cooperation between partners at regional, national and local levels, and those who work across all parts of the education system.

Partners must work together to:

1 Support regional and national partners to strengthen and link education monitoring systems to more effectively capture the full extent of disadvantage for girls and the ultra-marginalised.

2 Support ASEAN countries to meet the Education 2030 expenditure targets of 4% of GDP and/or 15% of national expenditure.

3 Support governments to implement strategies that channel resources directly to those students most in need, such as through cash transfers, scholarships and equity-based school grants initiatives.

4 Invest in long term initiatives that move beyond a focus on enrolment to one of student engagement and productive learning.

5 Strengthen school and teacher capacity and skills to detect and act on low learning and student disengagement.

6 Invest in secondary education initiatives to increase student enrolment and completion.

7 Develop targeted initiatives to reverse the recent drop in early primary enrolment.

8 Engage schools, parents and communities to improve learning and tackle harmful social norms and gender-based violence.

9 Ensure investments build on national systems and structures, take a ‘do-no-harm' approach and build in robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to understand impact.

10 Build a common research and knowledge exchange platform in the ASEAN region to identify high potential initiatives that can work at scale.

More research

Learn more about the challenges facing girls and women in the ASEAN region and opportunities to better support them.

This study has been conducted by the Australian Council for Educational Research

as part of the ASEAN-UK SAGE Programme thematic pillar studies. ASEAN-UK SAGE is an ASEAN cooperation programme funded by UK International Development from the UK government.